TEMPORARY PENETRABLE EXHIBITION SPACES (T.P.E.S.) (2003)

——

2005–2015 / interventions / various locations

List of T.P.E.S:

T.P.E.S. 00 (2005)

T.P.E.S. 01 (2005)

T.P.E.S. 02 (2005)

T.P.E.S. 03 (2006)

T.P.E.S. 04 (2008)

T.P.E.S. 05 (2009)

T.P.E.S. 06 (2011)

T.P.E.S. 07(1/2/3) (2013)

T.P.E.S. 08 (2014)

T.P.E.S. 09 (2015)

T.P.E.S. 02 Revisited (2023)

List of T.P.E.S:

T.P.E.S. 00 (2005)

T.P.E.S. 01 (2005)

T.P.E.S. 02 (2005)

T.P.E.S. 03 (2006)

T.P.E.S. 04 (2008)

T.P.E.S. 05 (2009)

T.P.E.S. 06 (2011)

T.P.E.S. 07(1/2/3) (2013)

T.P.E.S. 08 (2014)

T.P.E.S. 09 (2015)

T.P.E.S. 02 Revisited (2023)

The T.P.E.S.’s are site-specific interventions that occur in vacant disused spaces. Like many cities in Belgium, the city of Antwerp has many derelict, vacant buildings and spaces. These spaces are sometimes inhabited by the homeless. As a result these buildings are typically demolished by developers and city councils as quickly as possible. What is not generally acknowledged is that these deteriorated spaces serve an important function in the memory and social landscape of the city and in a way possess a beauty of their own. The rapid measures taken to demolish these unused spaces are a way to exclude everything that is irrational, chaotic and seemingly unreasonable in urban planning. Philippe Van Wolputte’s interventions draw attention to the existence of these spaces by making them accessible again for a short period of time, and he approaches his subjects with an almost Freudian-like obsession. Using narrow corridors and holes, he creates new passageways and infiltrates nearly impenetrable spaces, giving them a new temporary function as a fictional exhibition space.

The Temporary Penetrable Exhibition Space (T.P.E.S.) project is a way to research and deal with the difficulties of bringing the public to interventions in the public space. By exploring different scenarios the project tries to discover the best way, situation or site for bringing the public from ‘Point A’ to ‘Point B’.

For each T.P.E.S, a different ‘Point A’ is chosen:

Point A

– the street / word-of-mouth invitation T.P.E.S. 01

– the home / email invitation T.P.E.S. 02

– an artist-run space T.P.E.S. 03

– a gallery T.P.E.S. 04

– a private viewing T.P.E.S. 05

– an art festival T.P.E.S. 06

– an open studio T.P.E.S. 07 (1)

– a lecture T.P.E.S. 07 (2)

– a video screening T.P.E.S. 07 (3)

– a residency programme T.P.E.S. 08

– a publication T.P.E.S. 09

– ...

– the street / word-of-mouth invitation T.P.E.S. 01

– the home / email invitation T.P.E.S. 02

– an artist-run space T.P.E.S. 03

– a gallery T.P.E.S. 04

– a private viewing T.P.E.S. 05

– an art festival T.P.E.S. 06

– an open studio T.P.E.S. 07 (1)

– a lecture T.P.E.S. 07 (2)

– a video screening T.P.E.S. 07 (3)

– a residency programme T.P.E.S. 08

– a publication T.P.E.S. 09

– ...

The Points B, the Temporary Penetrable Exhibition Spaces themselves, are temporarily reopened locations that will soon be demolished or renovated, were previously unaccessible or have just been forgotten about in general, which deserve a (final) visit.

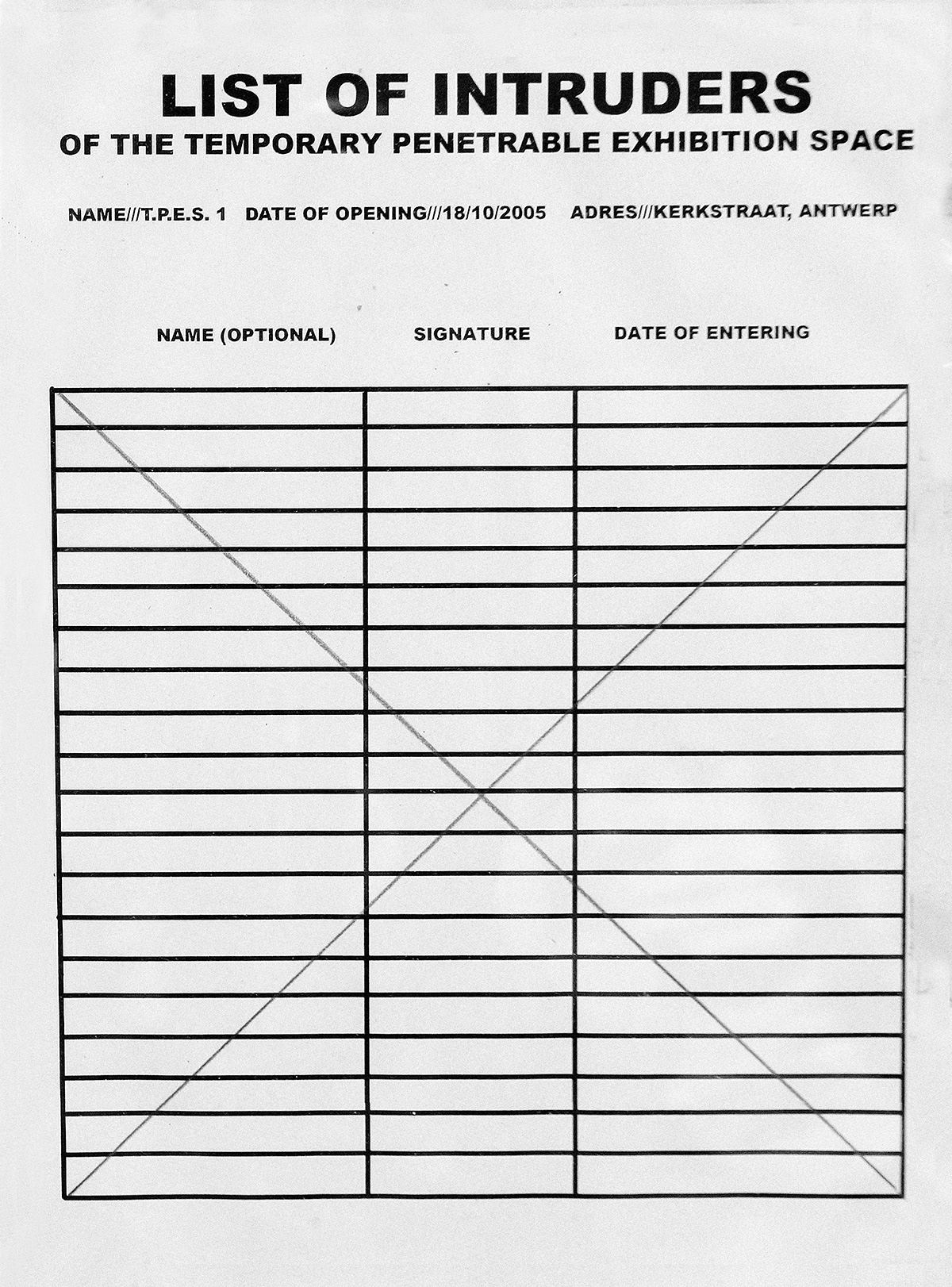

Viewers start out in the situation of Point A and receive a small flyer with coordinates to the T.P.E.S. location. In each situation, they are free to decide when or how to visit the T.P.E.S. location. Once people get close to the location, they are guided towards the entrance with the help of small indication arrows or other small interventions. Once inside, viewers are greeted by a poster reading ‘List of Intruders’, which can be signed. The interior is as-is. Nothing has been altered: what is exhibited is the space itself.

Traces of Absence - On Philippe Van Wolputte’s T.P.E.S. (2005–2015)

Like all big cities, it consisted of irregularity, change, sliding forward, not keeping in step, collisions of things and affairs, and fathomless points of silence in between, of paved ways and wilderness, of one great rhythmic throb and the perpetual discord and dislocation of all opposing rhythms, and as a whole resembled a seething, bubbling fluid in a vessel consisting of the solid materials of buildings, laws, regulations, and historical traditions. -Robert Musil 1

Temporary Penetrable Exhibition Space (T.P.E.S.) is a long-term project that spans over a decade, consisting of various site-specific interventions in the public or semi-public space. The majority of these temporary, ephemeral actions are clandestine or illegal, and have therefore gone unnoticed by many visitors or passers-by. By deliberately blurring the lines between fact and fiction, Philippe Van Wolputte creates situations where production and documentation become mutually implicated. As such, they reflect the complicated way in which we use archive material as an access point to invoke a bygone art historical reality, thus often mythologizing its nature. Where does the work begin or end; what are its boundaries? Did the interventions actually take place or are they carefully staged? Are we even able to tell the difference? Can we still ‘visit’ these historical sites retrospectively, and how does urban memory work? The whole T.P.E.S. project concluded with a solo show at

M HKA, where images of its different iterations were put on display. As the final chapter of this long-term undertaking, the exhibition itself was a further articulation of the constant dialectics between construction and reconstruction. Only now, in retrospect, could we start tracing back the origins of this project, in search of recurrent motifs.

M HKA, where images of its different iterations were put on display. As the final chapter of this long-term undertaking, the exhibition itself was a further articulation of the constant dialectics between construction and reconstruction. Only now, in retrospect, could we start tracing back the origins of this project, in search of recurrent motifs.

Breaking and entering

One apparent motif in Van Wolputte’s work is that of the grid. In fact, the grid has been there since the very first T.P.E.S., where it was applied using ordinary white paint and a long wooden stick. After that, we also see installations with spray-painted grids on large plastic sheets. The bluntness of their application and the physical directness of the gesture seem far removed from the formal rigidity of the modernist grid, as analyzed by Rosalind Krauss. Krauss argues that, understood in a spatial way, ‘the grid states the autonomy of the realm of art’. Its overall organization is ‘flattened, geometricized, ordered, [...] anti-natural, anti-mimetic, anti-real’.2 Instead, Van Wolputte’s grids are concrete motifs evocative of urban structures, such as fences and lattices, that are used to demarcate and secure certain areas, intended to keep intruders and trespassers out. In several instances, the grid motifs become juxtaposed with the spider-web-like structure of urban maps.

As the title indicates, most of the T.P.E.S. editions are temporary; not only in terms of visitor access but also due to the fact that the structures themselves will either become demolished or refurbished. In this sense, Van Wolputte’s ten-year project perpetually engages with processes of gentrification, always one step ahead of urban renewal and decay. As most of it has already vanished, the remaining documentation becomes a ghostly trace of an absent, bygone reality. A vague memory of what once was.

One of the first T.P.E.S. editions occurred in 2005. Still a student in Antwerp at the time, Van Wolputte intended to create his first ‘solo show’ by illicitly entering an abandoned building right across from the campus. The artist entered the building at night, covering all the windows with rasterized plastic sheets. Black graffiti at the entrance read ‘Ingang/Entrance’, ‘from 18 Oct till 1 Nov / Penetrable Exhibition Space’. The text is merely an indicative gesture, highlighting the building’s presence and its accessibility for a limited amount of time. People actually entering the building would find a ‘list of intruders’ in a kind of grid-like template inviting them to scribble down their name, signature and date of entry. Since then, T.P.E.S. actions have been held in a wide variety of venues and contexts, ranging from minimal interventions to more elaborately staged settings. For the third edition, which took place in the artist-run space Factor 44 in Antwerp, the idea emerged of creating a base from which visitors could depart in order to locate and discover the actual spaces scattered around.

In 2008, on the occasion of his forthcoming solo show at the Wilfried Lentz gallery in Rotterdam, Van Wolputte decided to ‘open’ a run-down monument not far from the train station. Once part of a large-scale master plan for the renovation of the station and subsequent revaluation of the surrounding area, the structure had soon become a shelter for the homeless. With the gallery as a kind of ‘outpost’ (as it was called on the flyer), visitors were invited to set foot in the forgotten monument. Another T.P.E.S. was part of a symposium titled ‘Performing Politics I: Critical Spatial Practices in Art and Architecture’, organized by Eric Ellingsen and Alvaro Urbano at Olafur Eliasson’s Institut für Raumexperimente in Berlin (2012). In that same year, Van Wolputte made another installation during the open studios at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, where he chose to counteract the typically prestigious event by not opening his studio to visitors. Instead, he made a staircase out of recycled wood leading onto a small and unappealing yard on the backside of the building.

Looking Back While Walking Forward, the video piece included in the eponymous installation at BOZAR in Brussels (2013), also features a T.P.E.S. hidden in a silo in Charleroi. Otherwise inaccessible to visitors, the intervention only survives through this faux-documentary video featuring a group of unidentified characters breaking and entering into an industrial complex. The last two editions were presented in a more institutional setting. As part of an exchange project titled ‘Het Kanaal/Le Canal’, Van Wolputte’s work was shown at Kunsthal Extra City Antwerp (in collaboration with NICC) and Espace 251 Nord in Liège. Finally, the whole T.P.E.S. project was consolidated in a book and a joint retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art (M HKA) in Antwerp, where the dark, gloomy images eerily contrasted with the brightly lit white cube of the museum.

Urbanization and its discontents

Where the city is becoming a habitat for an ever-growing number of people, it is also an agonistic site of struggle for space involving multiple actors: citizens, project developers, property owners, real estate brokers, city councils and so on. In an attempt to transform the city into an appealing environment, that is to say, middle-class- and business-friendly, certain parts are intentionally hidden from view. The daily life of most citizens is subject to biopolitical power in a most literal sense, insofar as their bodies are being steered or directed, making only certain zones accessible while obliterating others. The increase in urban monitoring and surveillance, both by the police force and technology, is all too often justified by the delusional belief in the possibility of a public space that can be fully transparent. Just like the ideal of security, transparency is a modernist myth as it relies on neoliberal mechanisms of exclusion and repression.3 This kind of policy is rooted in a biomorphic illusion of seeing the city as a ‘healthy body’ where diseases and cancerous spots can be cured or removed. Deviant or dysfunctional spaces are situated at the margin of a normalized, disciplined society, and are often also the locus of social injustice, alienation and homelessness. They can function as a refuge for derelicts and misfits,4 the socially deprived living in poor conditions. These dilapidated and decaying edifices, the dwelling places of the Other, so to speak, are often hidden from public view by a façade. This is why the façade, in one form or another, acts as a kind of mask. ‘The façade comes from a world in which, by using masks well, one clearly separates the public from the private, increases the tension between the two and valorizes the difference.’5

Of course, there are still ways to resist the dominant, strategic powers that be.6 Eluding institutional, hegemonic structures of control can be achieved by creating temporary autonomous zones.7 Occupying and squatting can be seen as tactical ways to reclaim the public domain, as expressions of political protest against market-led housing or as related, socially inspired and anarchist gestures. These are apparent, physical acts of violence, whereby the performers can clearly be identified, localized and penalized by surveillance and monitoring techniques. This is what Žižek calls subjective violence.8 Objective violence, on the other hand, refers to the inherent, invisible violence of a system creating the framework that renders subjective violence possible and that consolidates the status quo of the existing political-economic power relations. Due to its systemic nature, objective violence is less easy to identify or single out. The latter also has serious implications on the level of political framing, understood as symbolical violence. It enables policy makers to reason away the urban inequality and deprivation of certain neighborhoods as self-inflicted, a result of the individuals’ own shortcomings and not as the outcome of inadequate policy, discrimination, ghettoization, polarization or exclusion.9 This perverted line of reasoning often becomes a thankful excuse to justify procedures of urban renewal and gentrification.

The architectural uncanny

Each instance of the T.P.E.S. project (2005-2015) installs a sense of disorientation or discomfort, inviting the visitor to leave his or her safety zone. Abandoned areas have always fascinated Van Wolputte, an interest that could easily date back to his upbringing. His family comes from Doel, a now deserted village threatened with complete demolition in order to make way for the further extension of the Port of Antwerp. Despite the protest of a large number of inhabitants, the demolition works were started in 2008, accompanied by an unseen riot police force. Still heavily contested, Doel now looks like a war-torn zone and has become a much-favoured spot for street artists. In recent years, Van Wolputte has deliberately refused to revisit the place, solely relying on documentation and his imagination, in order to avoid a physical confrontation with its current, depopulated state.

There is definitely something uncanny about this experience. As Freud noted in his 1919 essay, ‘this uncanny [unheimlich] place [...] is the entrance to the former home [heim] of all human beings, to the place where everyone dwelt once upon a time and in the beginning.’10 The frightfulness of this experience has everything to do with an unexpected, ghostly return of the repressed, something that was supposed to stay hidden and secret. This ‘unhomeliness’ is brought about by the unfamiliarization and estrangement of what was once familiar. The uncanny effect is often amplified by effacing the distinction between reality and imagination. To speak, then, of an ‘architectural uncanny’11 would have to be related to a return of the repressed.

As suggested above, our understanding of the urban space is highly ambivalent. On the one hand, the city is supposed to be a ‘healthy body’, monitored by complex forms of social and individual control. In this view, it would ideally have to take on the features of an ordered, rational grid: a utopian delusion that is fueled by the desire for power through transparency. On the other, this delusion of a bright, transparent space is doomed to be paired with its opposite, that is, obscurity or opacity. In Van Wolputte’s work, these two dimensions – bright and dark, transparent and opaque – are confronted in a complex, dialectical interplay. Inside and outside are mutually implicated, by not only making forgotten spaces accessible but also, for instance, bringing them into the museum.

Pieter Vermeulen (2015)